How Liquidation Preference Fuels Conflicts in Venture Capital

- 1.2K views

- 21 minute read

Liquidation preference has long been a staple in Venture Capital funding, serving as a financial safeguard for Investors. While it addresses real challenges around risk and financial returns, it's far from a panacea. The very structure that aims to protect Investor capital can become a breeding ground for conflicts between Venture Capitalists and Founders, and even among Venture Capitalists. The rising complexity and scale of Venture Capital deals further magnify these challenges, exposing the imperfections of this time-tested mechanism.

In this post, I dive deep into the mechanics of liquidation preference. I begin by explaining why liquidation preference exists and the different types that are commonly used. The core of the article focuses on unpacking the potential conflicts it can cause—both between Venture Capitalists and Founders, and among Venture Capitalists. Finally, I will outline some best practices for mitigating these conflicts and fostering more harmonious relationships in Venture Capital deals.

In This Post

- Understanding Liquidation Preference

- How Liquidation Preference Creates Conflict in Venture Capital

- Illustration: The Trados Case Study

- Liquidation Preference Misalignments: Bridging the Gap

- Conclusion: tl;dr

Accelerate Your Learning: Watch Our Webinar!

Don’t just read about it, immerse yourself in the content through our companion webinar for this post! Engage with a multimedia presentation, discover all the referenced sources, and have your questions answered live! Click the “Watch Now” button to access the webinar.

Understanding Liquidation Preference

This section comprehensively explains what liquidation preference is, how it functions, why it exists, and the different types.

What Is Liquidation Preference and How It Works

Liquidation preference is a critical but often misunderstood term in Venture Capital agreements. It establishes the payout order in the event of an exit, commonly called a "liquidity event," ensuring that Investors receive their investment returns before other equity holders.

This term is usually contractualized in the term sheet and later included in the investment documents, typically the shareholders' agreement, specifying how the payout is structured. Read the post below for more details on term sheet clauses and governance in VC.

The parameters often dictate that the Investor receives their initial investment back, or a multiple thereof, before any proceeds are distributed to other equity holders such as Founders and employees. For example, a 1x liquidation preference means that the Investor would get their initial investment back out of the exit proceeds before any other distributions occur. Higher multiples like 2x or 3x are less common but can also be negotiated, indicating that the Investor would receive two or three times their initial investment before others.

If there's money left over after the Venture Capitalists have received their liquidation preference, the remaining funds are typically distributed among other equity holders according to their ownership percentages. This distribution can either be straightforward or involve more complex calculations based on participation rights or other special conditions outlined in the investment agreement, detailed below.

Why Liquidation Preference Exists

Historically, liquidation preference was introduced to safeguard the interests of Venture Capitalists in "downside case" exit scenarios, i.e., when the startup would get acquired or go public at a lower valuation than initially anticipated. There were instances where, due to their "sweat equity" (defined below), Founders could walk away with millions even in such exits, while Investors incurred losses. Liquidation preference serves as a mechanism to ensure that Investors recoup their initial investment, or a multiple thereof, before the distribution of any remaining proceeds.

Additionally, liquidation preference gives Venture Capitalists leverage at the negotiation table, particularly in strategic exits. In cases where an acquirer might be tempted to offer a low upfront price to the Founders and compensate with a sizeable earn-out package, Venture Capitalists could find themselves excluded from these earn-outs. A liquidation preference ensures that Venture Capitalists are accounted for in such arrangements, helping to align the financial incentives of all parties involved.

Over time, liquidation preference has also evolved to serve as a counter-balance to high valuations. In competitive markets, startups often command high valuations, increasing the risk for Venture Capitalists who come on board that their return will come in low. A liquidation preference clause can partly mitigate this risk by "wiping out" the high valuation when the exit does not materialize as anticipated.

Go Further: Watch the webinar for detailed illustrations and calculations on liquidation preference

Participating, Non-Participating, Capped

Understanding the types of liquidation preferences can be crucial for both Founders and Venture Capitalists, as they strongly impact their payout.

Non-Participating Liquidation Preference: In this scenario, the Investor has the choice to either receive their liquidation preference or convert their preferred shares into common shares and partake in the distribution of remaining proceeds. They don't get to do both.

Participating Liquidation Preference: Here, the Investor receives their liquidation preference and also participates in the distribution of any remaining proceeds according to their ownership percentage. This can be particularly advantageous for Venture Capitalists but potentially detrimental for Founders and other equity holders.

Capped Participating Liquidation Preference: Sometimes, a cap is placed on the participating preference to limit the upside for the Investor. Once this cap is reached, the preferred shares convert to common shares, and the Investor participates pro-rata with other common shareholders. It is sometimes called a "kick-out feature."

Unlike a liquidation preference which is rarely negotiable with a VC, a participation preference is almost always negotiable.

Brad Feld - Foundry Group (Source: Feld.com)

In some cases, the preference is calculated as a multiple of the initial investment that the Investor made. For example, a 2x liquidation preference would mean the Investor gets back double their original investment before any other payouts. These structures are more common in pre-IPO rounds.

In other cases, the Investor demands a minimum "guaranteed" return (there is no guarantee in VC, where capital can be entirely wiped out) expressed as a compounded interest rate or IRR. Term sheets denominate it as a "cumulative dividend."

Each type of liquidation preference has its own pros and cons and can significantly impact the financial outcomes for both Venture Capitalists and Founders. Understanding these types is crucial before entering into any Venture Capital agreement.

How Liquidation Preference Creates Conflict in Venture Capital

While it aims to balance risk and reward, liquidation preference can create conflict between Founders and Venture Capitalists, and even among Venture Capitalists. In the following section, I describe the root causes of these conflicts, drawing from academic research, real-life case studies, and my experience as an Investor.

Misalignments between Founders and VCs

There are at least two potential conflicts between entrepreneurs and their financial shareholders.

Flat Spots

The first layer of tension arises when an exit doesn't look as promising as initially expected. In such cases, Venture Capitalists might be motivated to expedite the exit process at a price that ensures their liquidation preference is fully paid out. This situation may occur at the end of a fund's life, when GPs might be tempted to rush a sale to close the fund.

The urgency often leaves Founders and employees, who typically own common stock (sometimes alongside early Angel Investors), in a precarious situation where they may walk away with little to nothing. The misalignment between the two parties' financial incentives can result in rushed decisions and sometimes even lead to the failure of negotiations with potential acquirers.

Having a large amount of liquidation preferences sometimes creates “flat spots” where some investors become indifferent to the ultimate price you sell your company between wide ranges of outcomes.

Mark Suster - Upfront Ventures (source: His Awesome Blog)

Mark Suster's quote perfectly illustrates the complexities and potential conflicts arising from liquidation preferences in Venture Capital deals, particularly when there is a "flat spot." In Suster's scenario, a pre-existing Investor can be more inclined to sell the company at $30 million rather than $50 million because, due to the liquidation preference and the associated "flat spot," they stand to earn the same amount of money in either case.

Watch the webinar for a numerical example illustration of flat spots in VC.

Disincentives

Another conflict comes into play when liquidation preferences stack up too high. Founders often find themselves disheartened as they realize they might never reach an exit price that allows them to make money above the liquidation preference.

A cornerstone of entrepreneurship motivation is the concept of "skin in the game"—the Founders' personal commitment to the new venture, typically measured in financial terms. Most Investors expect that entrepreneurs who are financially committed to their startup are more likely to roll up their sleeves and do the hard work when the going gets tough.

The concept found backing in academic research. A recent study of over 1,200 U.S. entrepreneurs found that while the absolute dollar amount invested before launch does not significantly impact firm creation, the proportion of personal funds invested relative to the entrepreneur's net income positively affects venture success and persistence in the venture creation process.

Entrepreneurs who invest larger amounts as a proportion of their net income are more likely to succeed and are less likely to disengage from the process.

Frid, Wyman, & Gartner, 2015 (Source: Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal)

For many entrepreneurs, this investment is not in the form of cash but instead in the form of time, effort, and skills contributed to the company's development. The term "sweat equity" signifies hard work and dedication, emphasizing that this type of equity is earned through personal input rather than financial contribution.

However, even in Silicon Valley's "go big or go home" culture, there are limits to how far one can push. When Founders lose the incentive to aim for a big exit, the Venture Capitalists themselves face the risk of diminishing returns. This dissonance creates a situation where neither party feels they are likely to benefit from any impending exit, making the journey forward fraught with tension and skepticism.

Inter-VC Conflicts

In a multi-round funding scenario, conflicts can arise among Venture Capitalists from different rounds due to differing liquidation preferences. All preference holders are regrouped in what is commonly termed a "preference stack," leading to a complicated pecking order for payouts upon exit.

Why Late-Stage VC Firms Need Protection

The friction occurs when later-stage Investors demand a stronger liquidation preference, via a higher multiple or priority payment, to offset the higher valuation and perceived risk, thus disadvantaging earlier Investors.

In a recent exchange on LinkedIn after I first published this article, Alex Mans, President of Flyr Labs (a startup that raised close to $200 million with Peter Thiel and WestCap), shed light on the nuanced roles liquidation preferences play at different stages of a company's growth, even when all VCs have the same conditions on their liquidation preference.

He emphasizes that while early-stage investors benefit less from liquidation preferences, these financial structures become critical in later stages, especially in funding rounds north of $50 million. Late-stage VCs (Series C onward) must protect their downside due to a higher cost of capital and lower return expectations from any individual investment. The power law plays less in their favor as they typically invest in much higher valuations than early-stage Investors.

You need long-term supporting check writers around the table willing to value things well above where early stage investors came in. These late-stage investors need protection due to their returns profile.

Alex MAns - Flyr labs

Alex Mans also pointed out that without liquidation preferences in place during later-stage investment rounds, Founders may lack the motivation to push for a company valuation that surpasses the total amount of liquidation preferences owed to Investors.

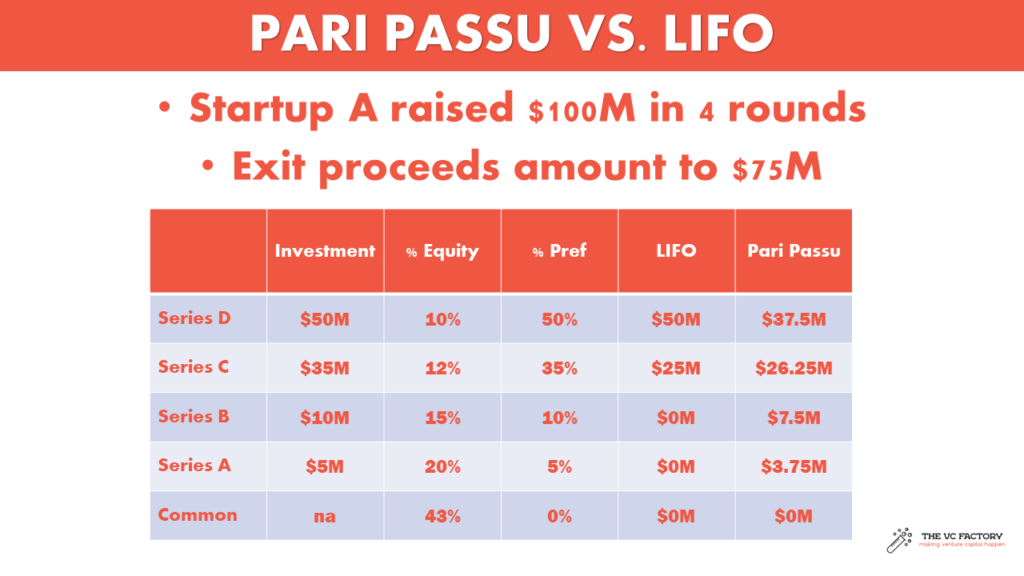

Exit Proceeds: Pari Passu vs. LIFO

VC firms agree to one of two mechanisms to divide the preference stack between them, depending on their bargaining power:

Pari Passu. In a pari passu arrangement, all Venture Capitalists are treated equally in the liquidation preference, irrespective of when they invested. Every Investor stands in line together, sharing proportionately in the liquidation proceeds. While this seems equitable, it can also create conflicts if later-stage Investors have invested at a higher valuation and yet find themselves on equal footing with earlier Investors, who arguably took higher risks by investing early. Note: this liquidation preference type is sometimes called "blended."

Last-in, First-out (LIFO). Although not traditionally called LIFO in Venture Capital (lawyers refer to it as "stacked liquidation preference"), this approach essentially means that Investors in the last round are the first to get their share of liquidation preference. Later-stage Investors who invest at higher valuations often negotiate for a more favorable position in the liquidation hierarchy to mitigate their higher risk. This structure, however, can be disadvantageous for early Investors, potentially causing friction among Venture Capitalists from different funding rounds.

1x non-participating and pari passu. This is a particular case. The pari passu feature works up to the total preferred amount. After that, some preferred shareholders may convert to common stock and take their pro-rata of the proceeds, given their lower entry price. Charles Yu illustrated this point with Palantir's prefs.

Illustration: The Trados Case Study

The tale of Trados encapsulates the dilemma of liquidation preferences in Venture Capital and serves as a cautionary tale for both Venture Capitalists and Founders alike. Despite a seemingly successful $60 million exit, common stockholders were left with nothing and decided to sue the VCs, accused of running a botched sale process.

The Trados case is far from rare: a company fails to yield the high returns anticipated, and the liquidation preferences set in place create a disproportionate distribution among shareholders. The litigation peeled back layers of the company's inner workings, providing rare and invaluable backstage data on boardroom dynamics, decision-making, and the actual impact of liquidation preferences.

This case sheds light on the complex interplay of interests that defines Venture Capital deals, offering vital lessons on the importance of equitable shareholder treatment and the intricate balance of power within a startup.

Trados: A Typical Middle-Case Scenario in VC

Founded in 1984, Trados became a $14-million software company by 2000, selling desktop solutions for document translation. Trados decided to raise funds in the Internet Bubble frenzy, aiming to accelerate growth ahead of a planned Initial Public Offering. Despite strong growth, subsequent funding rounds over two-and-a-half years didn’t yield Investor-pleasing results. By then, the Internet Bubble had burst, and the VC landscape had transformed. Many cash-strapped VC firms were looking for liquidity.

In 2005, Trados's financial shareholders orchestrated a sale to SDL, a UK-based competitor, for a reported price of $60 million. The exit left investors relatively unscathed due to their preferred shares, while common stockholders received zilch. The ensuing lawsuit questioned the fairness of the sale, alleging that the board had authorized an exit detrimental to common shareholders.

The plaintiff contended that instead of selling to SDL, the Board had a fiduciary duty to continue operating Trados independently in an effort to generate value for the common stock.

Final opinion dated August 16th, 2013 (Source: Delaware Court)

What’s most enlightening about the Trados case is the concept of “liquidation preference waterfall,” which describes who gets what in Venture Capital based on classes of stock and other contractual arrangements like Management Incentive Plans (MIPs). In this specific case, Venture Capitalists held both participating and non-participating preferred stock, rendering the type of liquidation preference moot since nothing was left once the preferred amount was paid.

Liquidation Preference Treats Shareholders Unevenly

According to Court documents, the Trados liquidation preference waterfall, illustrated below, had only two beneficiaries. Ultimately, the Venture Capitalists pocketed $49.2 million, far more than their total investment of $28.3 million, leaving common shareholders in the cold.

You've reached a Members-only area.

Unlock Full Access

Discover exclusive content curated for Venture Capital professionals and enthusiasts. Join our community and gain unlimited access to in-depth articles, expert guest interviews, MBA-level webinars, and networking opportunities.

Register for our 7-Day Free Trial: Click Here

Already a member? Please Log In Below:

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Join 12,000+ VCs & Founders globally who enjoy our weekly digest on Venture Capital. We keep your information confidential and you can unsubscribe at any time. Sweet!